Janet is a 65-year-old recently retired caterer who presents with a week of new dyspnoea on exertion, which is affecting her golf game.

She reports feeling otherwise well, with no fever, chest pain, cough or systemic symptoms.

She had a mild case of COVID-19 about a month ago, from which she recovered completely within a few days.

She is a lifelong non-smoker and usually enjoys robust good health, has well-controlled hypertension on an ARB and has no other history of note.

On examination Janet is afebrile with BP 128/83mmHg; heart rate 115bpm; respiratory rate of 20/min and oxygen saturation of 93% on room air.

Cardiorespiratory examination is unremarkable apart from a loud second heart sound and calves are soft and non-tender with no peripheral oedema.

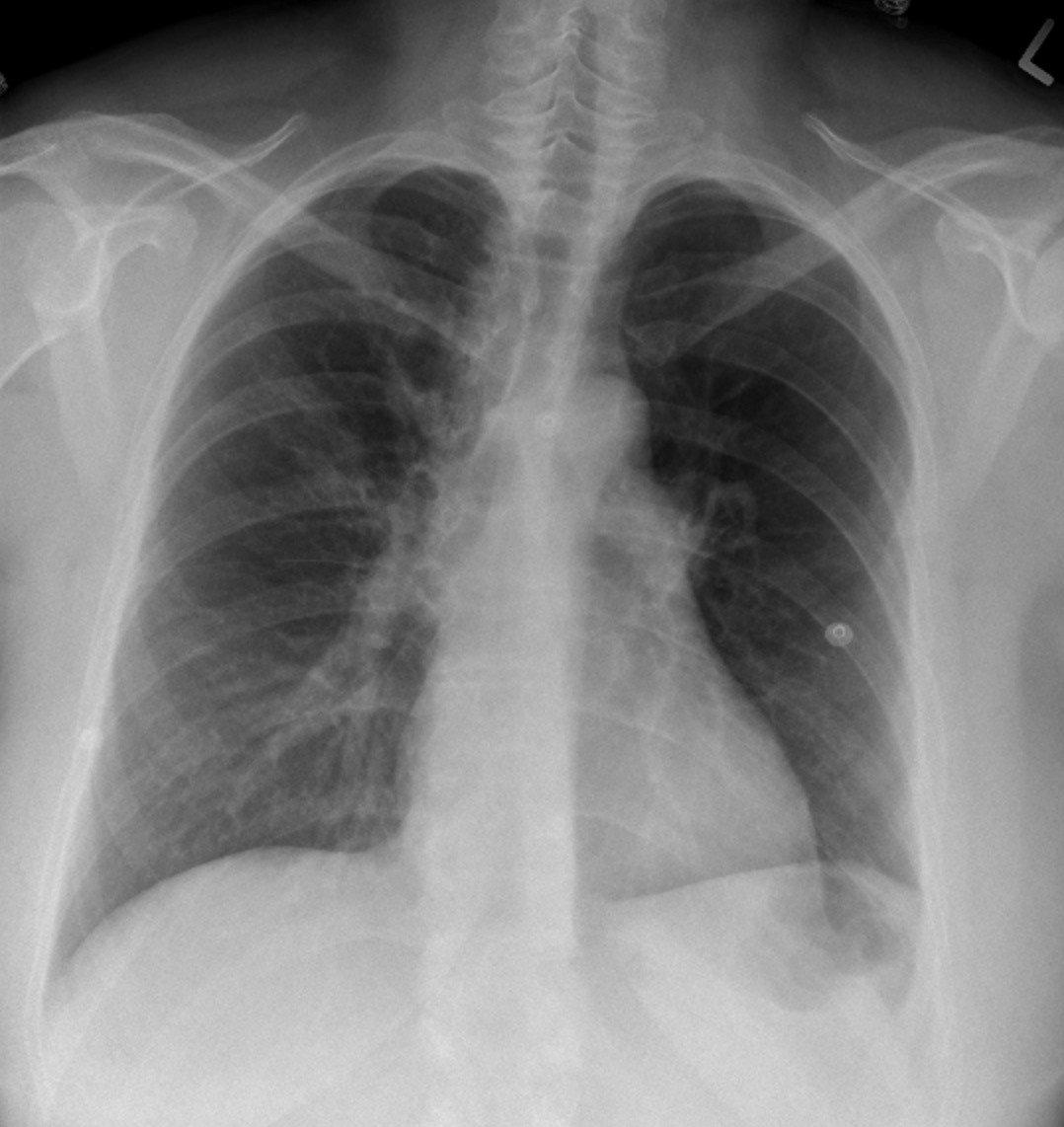

Chest X-ray is requested (pictured).

What is the most likely diagnosis?

Correct!

The chest X-ray demonstrates two suggestive radiographic findings for pulmonary embolism (PE): the Westermark sign in the right upper lung field and Fleischner sign (red arrow).

The Westermark sign describes focal increased peripheral lucency and loss of vascular shadows, thought to result from oligaemia secondary to pulmonary artery obstruction, or distal vasoconstriction in hypoxic lung.

The Fleischner sign describes a prominent, dilated central pulmonary artery radiographically, due to distension of the artery by pulmonary hypertension or a large thrombus. Both signs are highly specific for PE, though lack sensitivity.

The X-ray does not demonstrate suggestive features for congestive cardiac failure (cardiomegaly and enhanced vascular shadows, with or without pleural effusion), acute interstitial pneumonia (bilateral infiltrative and reticular shadows) or pneumothorax (visible visceral pleural edge, with absent lung markings peripherally).

Additional clinical clues for PE in this case include tachycardia and tachypnoea, with scant cardiorespiratory findings to suggest congestive cardiac failure, collapse or interstitial infiltration, and the loud second heart sound secondary to pulmonary hypertension. The recent history of COVID-19 points to potential for increased risk for hypercoagulability.

Much still needs to be clarified about the incidence and risk of post-COVID-19 VTE. Cases have been reported in patients following COVID-19 of varying severity, from mild to critical, and up to 180 days following acute infection.

It is still unclear whether PE following COVID-19 infection is a manifestation of long COVID. Also still to be determined is the critical risk period, after resolution of acute COVID-19, during which patients remain at high risk for VTE, as well as the pathophysiological drivers of any long-term procoagulant state post-infection.

In Janet’s case CT pulmonary angiography reveals bilateral contrast defects in the pulmonary arteries with right predominance, consistent with acute PE.

Prothrombotic workup is negative and there is no evidence of malignancy. Post-COVID-19 hypercoagulability is the working diagnosis as the cause of PE. Her symptoms resolve with anticoagulation.