Nicki is a 32-year-old who presents with three days of shortness of breath and right-sided pleuritic chest pain.

There is no associated cough, fever or recent URTI. Her past history is significant only for PCOS, requiring IVF for subfertility.

Nicki had her first fresh embryo transfer one week ago, uneventfully, but still feels bloated. There are no known VTE risk factors.

On examination, Nicki is afebrile, her respiratory rate is 22 breaths/minute, oxygen saturation is 95% on room air, heart rate is 110bpm and blood pressure is 112/80mmHg.

Chest auscultation reveals reduced breath sounds to the midzone on the right, with dullness to percussion.

Her calves are soft, non-tender and symmetrical. Her abdomen is mildly distended and tender.

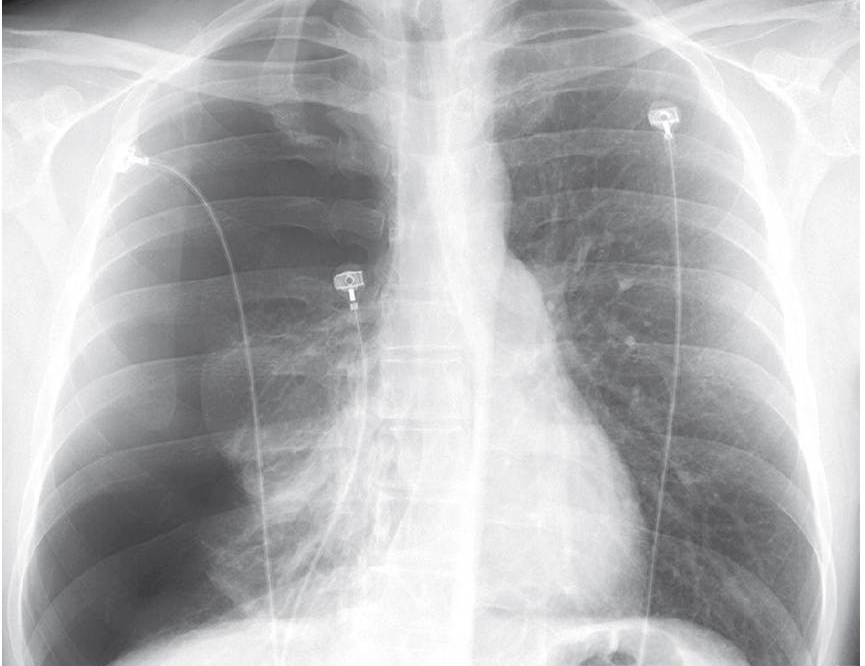

An ECG shows a sinus tachycardia. Nicki is referred for a chest X-ray (pictured).

What is the most likely diagnosis?

Correct!

The X-ray shows a large right-sided pleural effusion, with no pleural enhancement or tracheal deviation.

In the setting of recent IVF, fresh embryo transfer and PCOS, ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) is the most likely diagnosis.

OHSS is a complication of ovarian stimulation for assisted reproduction. It occurs in the setting of a robust ovarian response to gonadotropin stimulation — typically after human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) trigger administration to promote oocyte maturation prior to collection.

Successful pregnancy after embryo transfer, with associated rising placental hCG, may lead to OHSS persistence and worsening.

Exogenous hCG causes ovarian granulosa cells to luteinise en masse, which results in production of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and other proinflammatory mediators.

In excess, these can increase vascular permeability, leading to loss of intravascular fluid into the third space — typically around the ovary and in the peritoneal cavity.

The clinical severity of OHSS can range from mild abdominal discomfort and bloating to frank ascites, pleural and pericardial effusion, and hypovolaemic shock with haemoconcentration and risk of thrombosis.

Pregnancies complicated by OHSS may be at increased risk of pre-eclampsia and preterm delivery.

Risk factors for OHSS include a past history of the condition, PCOS and high antral follicle count and oestrogen levels with stimulation, as well as hCG trigger use and pregnancy after transfer. The incidence of clinically significant OHSS is 2-3%.

Moderate and severe cases of OHSS associated with IVF have decreased with modern IVF approaches, including use of gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist triggers.

The diagnosis is clinical, and management depends on severity. Mild OHSS can be treated with oral rehydration and simple analgesia (avoiding NSAIDs given the potential for acute kidney injury with intravascular depletion).

Severe OHSS may require inpatient management for IV fluid replacement, haemodynamic monitoring and thromboprophylaxis. Ascites and pleural effusion may require drainage.

In this case, Nicki’s GP contacts her treating fertility team, which admits her. Transvaginal ultrasound shows significantly enlarged ovaries, with a small amount of ascites.

A chest drain removes 5L of serous fluid, with symptomatic relief. Nicki is discharged five days later and goes on to deliver a healthy baby girl at 39 weeks’ gestation after an uncomplicated pregnancy.